20 Jul A Workshop on Mapping Frames for strategic Action

Overview

This article documents and shares insights from a design research workshop to ‘Map Frames for Strategic Action’, hosted on 26th May 2021, with invited participants from a community of ‘new economy’ activists in the UK, as well as academics with expertise in areas of design, economics, sustainability, participation, peer-to-peer, commons and political economy.

The purpose was to explore how a better understanding of socio-political framing can support design for strategic action, through hands-on design activities emphasising the embodied and material dimensions of frames.

We commenced the workshop by presenting our project focus: to understand the relationship between socio-political framing and strategic action in the field of sustainability, to develop a novel design approach for social change. Specifically, our work has been focusing on the movement for ‘new economics’, which we take to mean innovative community-led approaches to sustaining livelihoods and wellbeing. We see ‘sustainability’ as an intersecting set of issues concerning multiple communities, including marginalised groups.

We introduced our project partners, Citizens UK, Public Works and ECHO; the academic project mentors Prof John Wood, Prof Paul Rodgers, Dr Kersty Hobson, Prof Tracy Bhamra and Prof Thomas Tufte; and the project research undertaken to-date through interviews, critical discourse analysis and desk research focused on new economy organising. You can view the slides used on the day here.

The workshop activities were run on Zoom and MIRO and involved four design research activities. Participants worked in groups together to build up layers of information according to each step. Each step was guided by some instructions and questions. Participants worked together through the activities, sometimes adapting or circumventing the initial instructions. What follows are reflections and insights specific to community organising practitioners working with frames, as well as outcomes that will inform our next steps.

Context and Set-Up: New Economics

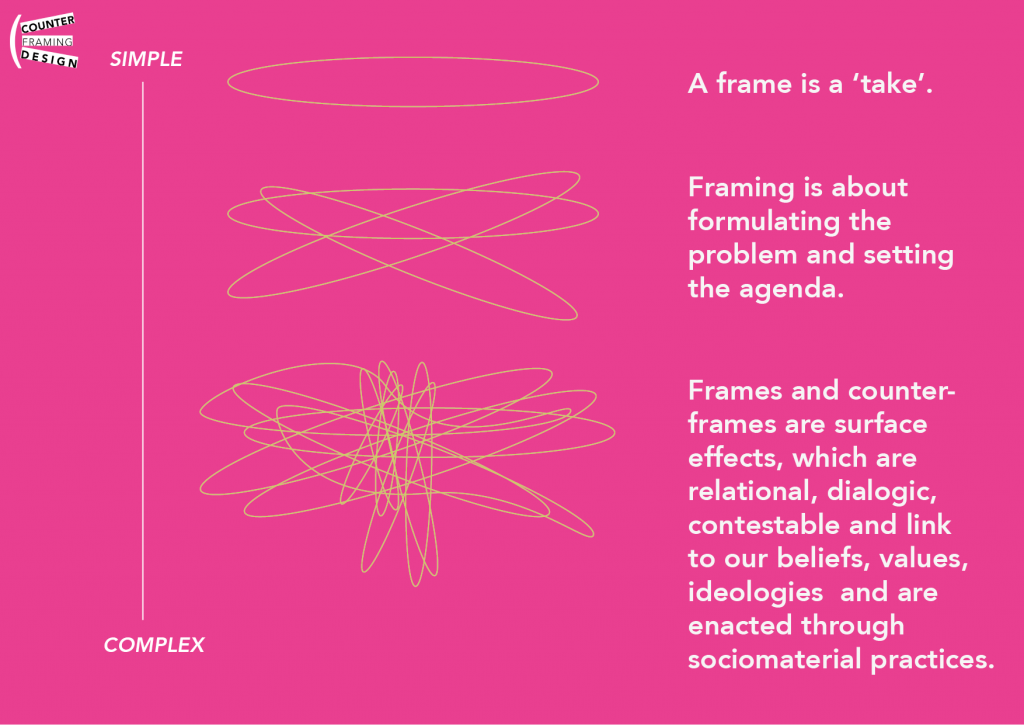

We set the agenda for the day by sharing initial insights on our research undertaken to-date and posing questions in relation to some of the emerging discourse of new economics. We provided a brief introduction to frames and counter-frames as well as some examples from the community of practitioners.

For instance,

- the 2018 NEON, NEF, PIRC, Frameworks Institute report ‘Framing the Economy’ report featured research into common frames that reveal the economy as a cognitive hole or ‘black box’ in the popular imagination;

- whilst the concept of the embedded economy, as popularised in Kate Raworth’s wildly influential ‘Doughnut Economics’, is seen as keeping the black box intact by some theorists;2

- meanwhile, Hilary Cottam’s Welfare 5.0 report comments on the prioritisation of economic over social structures post-Covid, thus revealing their separation.

As lecturer in economic philosophy Alex Douglas says, ‘the challenge is to break out of the paradigm’.3 Interviews undertaken for the Counter-Framing Design project have emphasised the social and community relations constituting the emerging new economy. As design researchers, our focus is how we can use design and creative methods to support the challenges to envision things differently.

Activities

Activities 1&2: Object Framing & Mapping

The goal of our first set of activities was for participants to introduce themselves and their organisations and practices whilst beginning to identify some of the frames that emerge in their work, harnessing these within material objects.

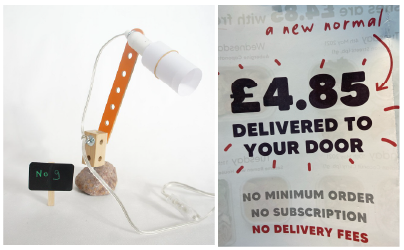

Prior to the workshop, we invited participants to bring an object that represents an aspect of their practice, either positive or negative. It could be a cup, a t-shirt, a toy, or a hand tool.8 For example, Sharon chose this ‘low-tech’ lamp, and Pandora chose this ‘new normal’ pamphlet:

Right, authors.

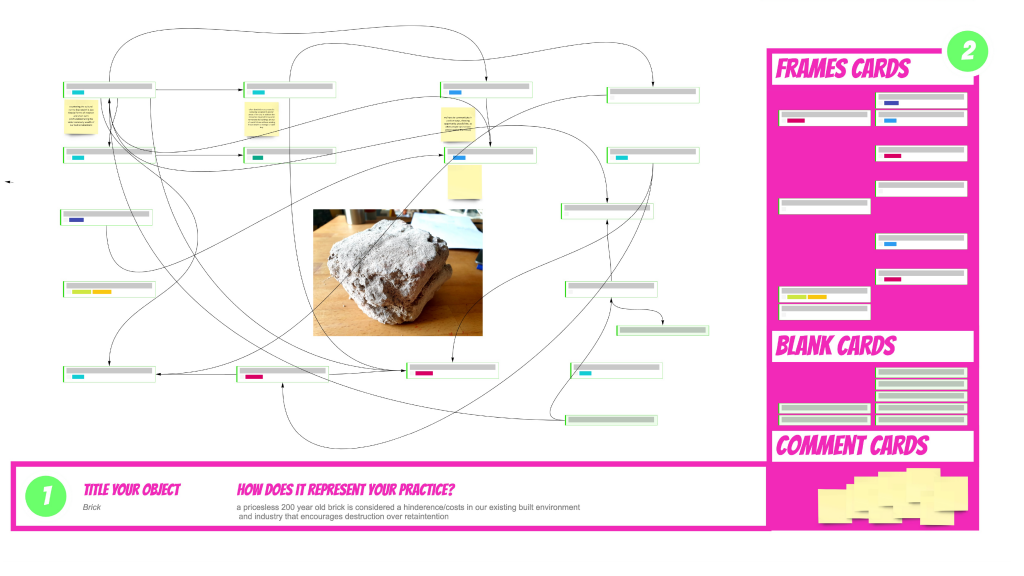

Participants were asked to map frames onto their object of choice on an individual ‘place setting’ in a group Miro board, with four participants per group. As well as dragging and dropping any relevant pre-filled ‘frame cards’ from a list of around 30, based on our research to date, participants were encouraged to add their own frames using blank cards, and to add comments to elaborate on any reasons for choosing certain frames or the connections therein. Finally, they were asked to map relationships between frames by clustering them and drawing connecting lines.

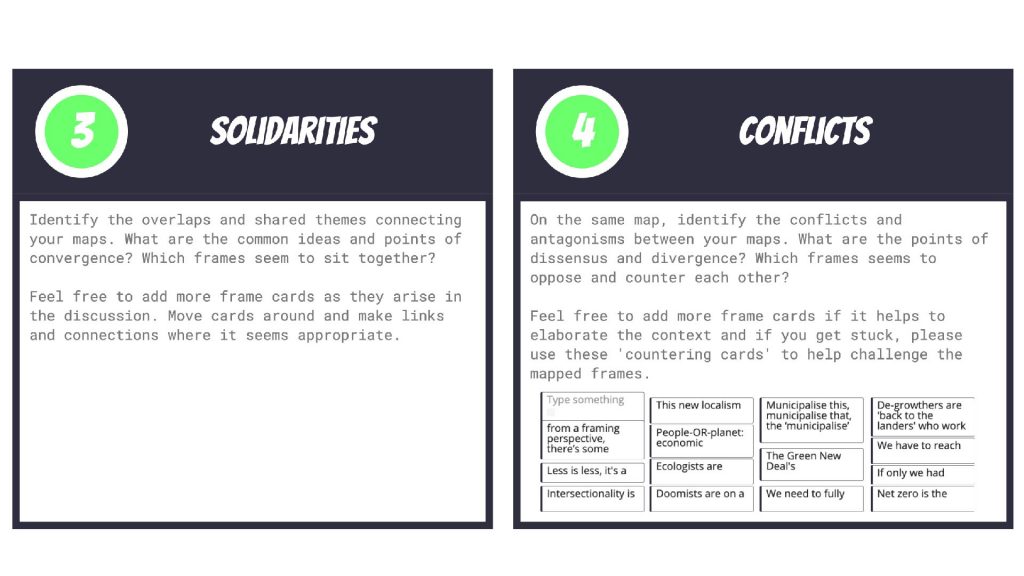

Activities 3&4: Solidarities & Conflicts

For activity three, we asked participants to identify and build on the overlaps and shared themes between their individual frame maps. In activity four we asked them to explore the conflicts and antagonisms that came up within and between frames. The intention was to use design research to explore mechanisms of counter-framing we had identified as: time, scale, embodiment, intersectionality and metaphor. We presented these mechanisms with ‘countering cards’, which dissented against some of the frames identified.

Insights and Reflections

In this section, we share early analysis organised thematically according to an excerpt from a draft typology of frames on new economics; frame clusters; resonant frames; contradictory, co-opted or divisive frames; and finally, frames of solidarity.

Frame Categories, Hierarchies, and Interdependencies

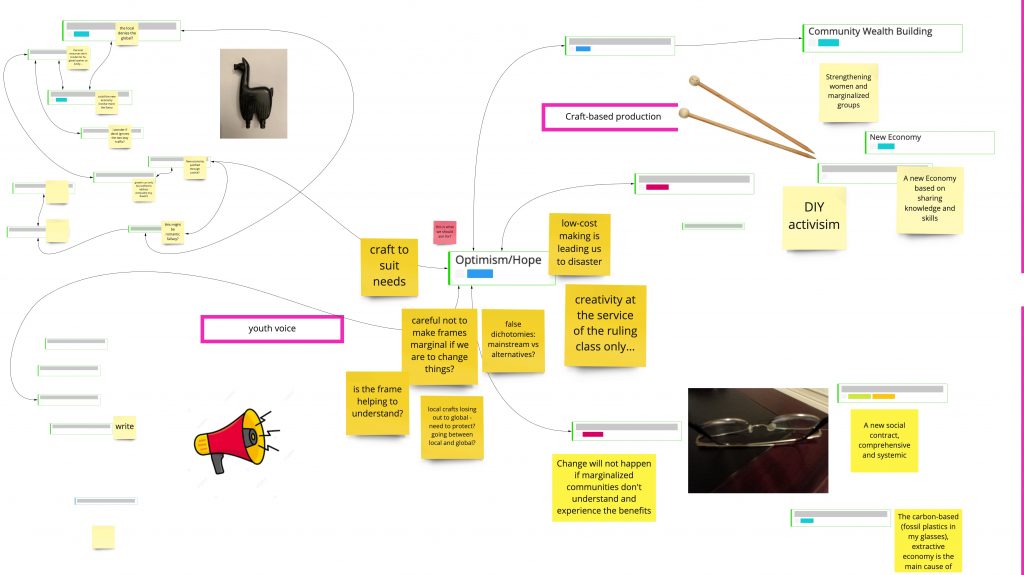

The summary of frame cards generated during activity one shows the most prominent frames as anti-capitalism, sustainable and inclusive growth, community wealth building, people and planet, new economy and optimism/hope. Within this cluster of frames are many contradictory ideas. Other frames that are prominent include wealth inequality, fairness, green new deal, guerilla localism, climate justice, converging crises and pragmatism. Most of the frames provided were used at least once, and some new frames were created by participants, notably: DIY activism, local knows best, people power, land justice, heritage and peer-to-peer. Interestingly, sustainability itself was a relatively unpopular frame. This reflects our research findings, in which interviewees5 said they found the term unhelpful as it has been rendered meaningless by overuse and co-option by corporate powers.

In our (draft) typology of frames (excerpt in Table 1), we have developed a working categorisation of frames. ‘Response frames’ include those that respond to climate and interlinked crises or Covid, such as optimism/hope or pragmatism. ‘Master frames’6 are recurring frames under which other frames may fall, an example being the fairness or rights frame, encompassing the right to repair, civil rights, women’s rights and rights of nature frames. ‘Localism frames’ include community wealth building, and ‘naturalised frames’, such as wealth inequality, where there is a degree of supposed normativity or ‘common sense’. These various frame types regularly intersect.

| Frame Type | Description | Example |

| Response | Response frames connote a mindset or response to scenarios actualised through terms such as ‘adaptation’, ‘deep adaptation’, ‘climate action’ or ‘climate denial’ or ‘localism’ | Optimism/hope, alongside doom/fatalism and ‘pragmatism’ |

| Master | In social movements studies, master frames are persistent frames that reappear time-and-again through cycles of protest, including variations on the ‘rights frame’. | Rights frame Anti-capitalism |

| Naturalised / Institutionalised | In these frames there is a degree of cultural ‘common sense’ or implicit acceptance of the frame. These are often targeted by counter-frames, which seek to de-normalise. | Wealth Inequality Law and Order |

| Collective Action | Collective action frames offer strategic and intentional interpretations of issues with the intention of mobilising people to act (counter-frames may or may not be collective action frames) | Anti-capitalism New Economy |

These different frames act variously on policy, mindsets, communities and social groups or broader society and the government and as such work at different scales. Our draft typology is a step towards understanding the hierarchies that exist between frames and their interdependencies. For instance, localism might also be understood as a response frame, when it is interpreted as a type of ‘retreat’ from global issues.

Frame Debates

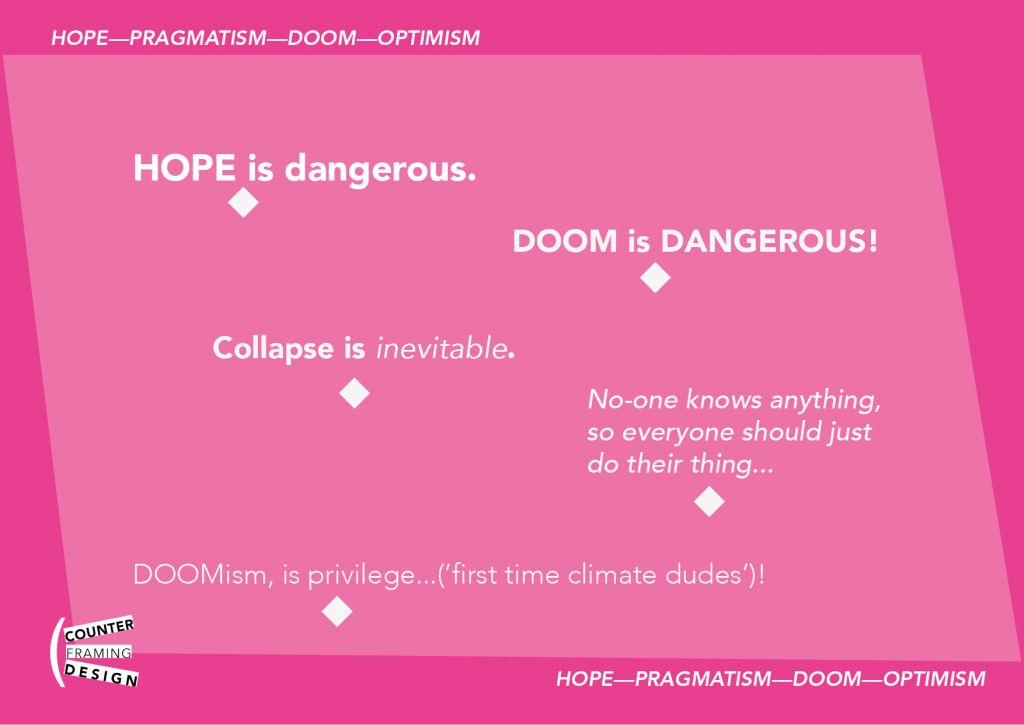

This speaks to the complexity of frames, which we introduced through some of the frame debates we have identified in our research so far, for example concerning the optimism/hope frame with regards to climate and dissenting ‘doomist’ frames, the conflicts therein revolving around the timescale of ecological and societal breakdown and the privileged position of those who can choose to retreat, or even profit from collapse narratives. Another cluster of response frames we have identified emerges around the idea of ‘going back to normal’ or the ‘new normal’ in contrast with countering frames such as ‘build back better’ (which has subsequently been co-opted by conservative politics) and ‘normal wasn’t working’, a frame which challenges the upholding of normal as a privileged and ultimately placating position.

Through the workshop, a new frame cluster was identified within the emerging ‘new economy’ discourse and includes the frames of ‘community wealth building’, ‘community wealth’ and ‘wealth inequality’. Some interviewees problematised the naturalised frame of ‘wealth inequality’ as a red herring in lieu of which ‘assets’ and ‘debt’ should stand. For instance, one interviewee spoke of ‘monetary inequality’ to address ‘liquid money’ as a preferable frame to ‘wealth inequality’. Others proposed to reclaim the meaning of ‘wealth’, as relating to sources of happiness and wellbeing. Or how issues and frames might be bridged through ideas of ‘health inequality’ or ‘mental wealth’.7 These new economy frames are selective and reflective of the participants we have engaged.

Resonant and Dissonant Frames

Activities resulted in insightful discussions within groups around what constitutes a frame and their characteristics. The discussion touched on how frames are subverted (or in our term, ‘countered’) to gain mass appeal – for example the right to repair is a more resonant mobilising frame than circular economy – whether frames are unconscious or strategic or both, and how frames may fluctuate or move along a spectrum at different points in time in a group’s work. Frame resonance is an important concept in the literature. Simplistically, this requires considering aspects such as credibility of the frame makers (expertise, charisma, credentials), the properties of a given frame (consistency, cultural relevance), and the political, moral and ideological orientation of frame receivers.8

The object activity facilitated insights into the complexity of the socio-material and socio-political systems around frames to transcend the field of practice, in which organisers typically limit their practices of framing to a form of sloganeering. Frames are understood to ‘script’ behaviour in our daily lives, meaning simply they can determine the roles we play. For example, that several people’s objects represented mass-produced tools, which are in direct conflict with the ideals of their work, generated reflection on this type of dissonance, which is also reflected in the seeming contradiction between the top frames of anti-capitalism and sustainable and inclusive growth – represented, for example, by one participant’s object, a selection of seeds and pulses. Similarly, localist frames face challenges when applied at a larger societal scale. To this end, the object activity offers opportunities to elaborate on hierarchies, interdependencies and sources of dissonance in making frames and as such conceive of more resonant and thereby effective frames.

Contradictory, Co-opted and Divisive Frames

In addition to the frames identified and created, participants discussed inclusion and boundaries and the nature of collaboration. Frames can be contradictory within a single context, co-opted and divisive. Many considered the power of hope and optimism, and of acting locally. However, these discussions also gave rise to reflection on the contradictions that emerge, for example tensions between pragmatism and system transformation, and between system change and a romantic ‘retreat’ to localism. Others discussed how frames can extend from schematic to pragmatic, from idealist to personal, as well as how they are tailored to different audiences. Furthermore, participants discussed how frames can backfire, for example within immigration discourse, ‘no one is illegal’ may be said to either naturalise or validate the illegal frame, in a similar vein to criticisms of the degrowth frame validating growth9. Participants also reflected on the co-option of frames as a strategy within capitalism in the face of subdivisions on the left according to identity frames, which fragment and distance grassroots organising from larger shared goals of (for example) community wealth building and reducing inequality. However, such generalised frames can erase difference, leading to further marginalisation for certain groups.

Frames and Strategies for Solidarity

On the other hand, one participant commented that if we’re to see beyond the black box, we must account for how we envision the other’s imagination. In the literature, the idea of building solidarities across communities by connecting agendas and issues is known as ‘frame bridging’.10 How we materialise frames (for example through the object activity) may offer ways to respond to this need, because of how objects can elicit the cultural as well as scripting nature of frames. The scripting capacity of frames is well understood in the literature and simply means that different frames elicit different behaviours or roles (by providing a ’script’ for ’a role’) in different contexts.11

Furthermore, the tensions between theorising and idealising activism and making an impact on the ground through pragmatic action was a key discussion point and central to the purpose of the workshop, which brought together academics and campaigners. Participants also discussed how frames can fluctuate from pragmatic to utopian and even sometimes dystopic.

These discussions speak to where broader coalitions might be meaningful, as well as to what meaningful compromises may look like against instrumental framing strategies. For instance, the ‘radical’ frame (in our project used in the proper sense of the term, meaning to get to the root of the problem) is pitted against pragmatic practices. At the same time, ‘seeking to be successful in terms used by institutional power holders will always carry costs in marginalising certain frames and the real needs they express’.12 In many cases, those supposed marginalised frames have not been understood as radical in recent memory (e.g., anti-racism), in the popular political meaning of the word. To this end lawyer and activist Dean Spade offers guiding questions relevant for strategic action for community solidarity that may aid community activists in this respect:

- ‘Does it provide material relief?’

- ‘Does it leave out an especially marginalised part of the effected group?

- ‘Does it expand a system we are trying to dismantle?’

- ‘Does it mobilise people, especially those most directly impacted, for ongoing struggle?’17

Key Outcomes and Next Steps:

Further Work

Other important questions to emerge during the session were:

- How can we anticipate unintended consequences of frames?

- How can frames shirk marginal positions?

- How can we understand if frames are obfuscating or illuminating?

- How can frames respond to and prioritise feelings, rather than instrumentalise or exploit them?

- How can frames help to navigate between pluralism and the disintegration of a movement?

- How to prevent the co-option of frames?

- Equally, how to gain popular appeal without being co-opted?

While this set of activities yielded interesting and useful results as far as the above, it did not prove useful for generating new frames. Participants found the instructions and online format to be complex and part of that discussion and feedback informs improvements in the methodology used on the day, to support the activities, methods and countering mechanisms devised and how they can be harnessed to more effectively challenge dominant frames.

Overall, our design research activities generated insights on a range of practical and conceptual issues and themes. This includes community issues and challenges, including current frame debates (e.g., emerging new economy frame clusters relating to ‘wealth’), as well as grappling with the characteristics and nature of frames and framing processes.

Insights for practitioners relate to how:

- A (draft) typology of frames relevant to the emergent ‘new economy’ may support under standing movement positions and types of frames

- Identifying frame debates can be helpful for disentangling debates and positions within a movement, such as which frames might inadvertently validate a dominant frame

- Considering frame debates (e.g., ‘wealth’) against response frames (e.g., hope/doom) offers opportunities to interpret frames, how they might be co-opted or counter-productive

- Engaging with the materiality of frames supports understanding of how frames shape everyday practices, and as such can be useful for community organising

- A better understanding of framing can support strategies to win material gains now, without compromising broader social change, by seeking frames that don’t inadvertently foreclose further action.

Conceptual and methodological insights relate to how:

- Considering material dimensions of frames, as well as discursive, aids understanding of the complexity of frames, such as how frames play out in our daily lives, their ideological basis and how they elicit dissonance;

- Identifying and exploring frame debates could aid with anticipating contradictory frames, those which might easily be co-opted, be self-neutralising or prove divisive in unproductive ways;

- The potential of design research methods for eliciting understanding of the characteristics of frames and engaging in new frame-making practices and processes is evident in the breadth of insight here presented

As we develop a design approach based on counter-framing, we endeavour to continue to respond to some of these questions and issues.

Footnotes

[1] For more on theories of framing in relation to the project, including the distinction from ideology and discourse, see Prendeville, S. & Syperek, P. (2021), ‘Counter-Framing Design: Politics of the New Normal’, NORDES (forthcoming).

[2] Vidal, M., & Peck, J. (2012). Sociological Institutionalism and the Socially Constructed Economy. The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Economic Geography, 594–611. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118384497.ch38

[3] We’ve given a longer talk on Counter-Framing the New Economy, which you can view at: https://designandeconomics.com/2021/04/19/counter-framing-the-new-economy-hosted-by-sharon-prendeville/.

[4} This activity was inspired by Drazin’s ‘design concepts’ whereby cultural knowledge embedded in socio-material artefacts such as objects, recordings, texts, diagrams, video and visualisations offer a means through which the socio-political context of frames can be put into dialogue. Drazin, A. (2016). The Social Life of Concepts in Design Anthropology. In Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice (Vol. 23, pp. 1–11). https://doi.org/10.1111/gena.12013

[5] Interviewees and workshop participants were chosen purposefully based on their specific expertise and active practices, i.e., not through random sampling.

[6] Benford, R. D. (2013). Master Frame. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements, (Markowitz 2009). https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470674871.wbespm126

[7] See Dark Matter Labs (2021). ‘Building Mental Wealth’ https://provocations.darkmatterlabs.org/building-mental-wealth-34441f638e3b.

[8] Noakes, J. A., & Johnston, H. (2005). Frames of Protest: A Road Map to a Perspective. In Frames of Protest: Social Movements and the Framing Perspective (First). Oxford: Rowan and Littlefield Publishers Inc.

[9] Additionally, for commentary on this debate see: https://timotheeparrique.com/category/debate/

[10] Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 611–639. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

[11] Shank, Roger C. and Robert P. Abelson 1977. Scripts, Plans, Goals in Understanding: an inquiry into human knowledge. Hillsdale N.J.: Erlbaum.

[12] Ferree, M. M. (2003). Resonance and Radicalism: Feminist Framing in the Abortion Debates of the United States and Germany. American Journal of Sociology, 109(2), 304–344. https://doi.org/10.1086/378343

[13] Spade, D. (2020). Solidarity not charity: Mutual aid for mobilization and survival. Social Text, 38(1), 131–151. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-7971139